-40%

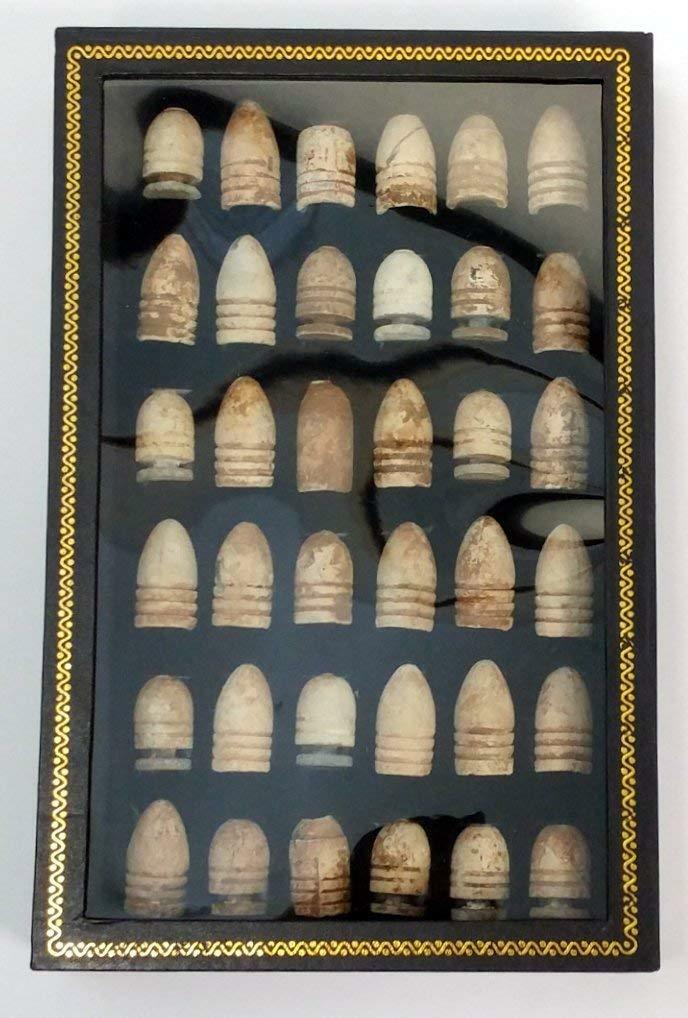

Battle of Nashville TN Civil War Relic Found Shy's Hill Drop 577 Enfield Bullet

$ 15.83

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

We are working as partners in conjunction with Gettysburg Relics to offer some very nice American Civil War relics for sale. The owner of Gettysburg Relics was the proprietor of Artifact at 777 on Cemetery Hill in Gettysburg for a number of years, and we are now selling exclusively on eBay.THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE / SHY'S

HILL / CONFEDERATE LINES - FROM THE WILLIAM A. REGER COLLECTION - A very nice dropped .577 Caliber Enfield Bullet with a cone cavity

This

Enfield Bullet

was a part of the old, well-identified collection of William A. Reger from Berks County Pennsylvania, who passed away in Reading, Pennsylvania in 2011. These artifacts were identified with a label that indicates that they were recovered in June, 1963 in the Confederate lines on Shy’s Hill at the site of the Battle of Nashville.

The collection was meticulously identified with relics and relic groups each having their own typed labels.

'It was at Shy's Hill on Dec. 16, 1864, during the Battle of Nashville, that Federal troops finally broke the Confederate line on the left flank, resulting in a massive Rebel retreat and a decisive Union victory.

A heavy day of fighting on Thursday, December 15, 1864, saw Confederate forces fall back to the south to an east-west line roughly parallel to the current course of Harding Place in South Nashville. The right flank of the Confederate line was anchored at Peach Orchard Hill to the east, and the left or western flank at Compton’s Hill, later to become known for posterity as Shy’s Hill.

Darkness, battle fatigue and terrain became significant obstacles as Hood’s army attempted to re-group to the south. Depletion from casualties resulted in a considerably shorter defensive line. On the west flank, Hood positioned Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s Corps on what he thought would be strategic high ground – the steep promontory of Compton’s Hill. Cheatham, a Nashville native, placed defense of the summit of Compton’s Hill in the hands of Maj. Gen. William B. Bate’s division, consisting (from left to right) of Tyler’s Brigade under the command of 25-year-old Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith, Finley’s Florida Brigade under the command of Maj. Glover Ball, and Jackson’s Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Henry Jackson.

Tough Odds for Hood’s Troops. Confederate troops occupying Compton’s Hill did so against staggering odds. They were outnumbered by an overwhelming Union force which had surrounded them with infantry to the north and west of the Hill, and with cavalry to the south.

Serious problems were facing the Confederate force as darkness descended on Thursday evening, December 15. As the first day’s action died down, Cheatham’s Corps had to deal with the combined disadvantages of darkness, muddy terrain, and the weariness of what had been a difficult day on the battlefield, especially on the Confederate left flank.

Cheatham, positioned on the Confederate right flank on December 15, had to move south and west from his position around Nolensville Pike and was late arriving at the high ground. Reestablishing their defenses in the dark created new problems. They dug all night with few tools and axes – a difficult task at night on the steep slope, and were able to cut some trees and pile rock to complement the works. The trenches, however, due either to darkness or miscalculations by the engineers, were inadvertently constructed too far back from the “military crest.” As a result, the steepness of the hill became a liability instead of providing a high-ground advantage, because when daylight came, they were unable to see down the slope far enough from their positions to fire at Federal troops charging up the hill until the attackers were almost in their lines.

In addition, the trench lines were set up by aligning with a fire on the grounds of the Bradford house to the northeast. When daylight came on Friday, December 16, the angle and direction of the trenches did not line up with Stewart’s Corps to the east at around Granny White Pike. An angry Cheatham had to quickly readjust the line to the south in order to link up with the remainder of the Confederate position which ran easterly toward Peach Orchard Hill.

Hood Moves Troops From Hill. As the day progressed, the already depleted Confederate force on the Hill was further reduced by Hood’s perceived need to move troops – four brigades in all — away from the hilltop. The first move occurred around noon, when the encroachment of Maj. Gen. James Wilson’s Union Calvary Corps from the south, behind the Confederate line, required Hood to shift Ector’s brigade of French’s Division, Stewarts Corps, to the south.

Next, furious fighting at Peach Orchard Hill caused Hood to move two brigades of Cleburne’s Division — Lowrey and Granbury — to the right flank in the afternoon. And finally, about the same time, Reynolds Brigade from Walthall’s Division, Stewarts Corps – posted to the right of Bate’s Division on the Hill – was moved south to support Ector. The summit line was left thin, with no reserves.

By late afternoon, with daylight beginning to fade on a rainy day, Federal commanding Gen. George Thomas had been unsuccessful in ordering Maj. Gen. John Schofield to organize an assault on the hill with his XXIII Corps. Growing impatient as the day grew darker, Federal Brig. Gen. John McArthur, division commander in Smith’s XVI Corps, saw the Union advantage gained during the day-long siege of the Confederate left flank slipping away, and that nightfall would enable Hood’s army to either strengthen or escape.

Federal Attack In Late Afternoon. At about 3:30 p.m. he sent a message to Thomas and XVI Corps commander Gen. Andrew Smith that unless he were given orders to the contrary in the next five minutes, his division was going to attack Compton’s Hill and the Confederate line immediately to its east. Receiving no response by his imposed deadline, he ordered the charge by three brigades which contained four regiments of Minnesotans, as well as troops from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

McArthur began the assault with only the First Brigade. Under the command of Col. William McMillen, they advanced under orders for silence and began the struggle directly up the severe north slope of Compton’s Hill, using the steepness as their cover. The 10th Minnesota Regiment, surging up the northeast side of the hill on the left end of the Union advance, was exposed to flanking fire and was hit hard. As the First advanced half way up the hill, McArthur sent the Second Brigade, with the 9th Minnesota on the right and the 5th Minnesota on the left. Its commander, Col. Lucius F. Hubbard, had two horses shot from under him and sustained a minie ball wound to the neck as the unit crossed a muddy corn field moving southwest. With their line exposed to enfilading fire, they sustained significant casualties including four 5th Minnesota color bearers who were shot down in the charge.

In short order, however, the 10th Minnesota breached the line of Finley’s Florida Brigade, and attacked Smith’s and Jackson’s Brigades from the rear. This precipitated the Confederate collapse. By the time McArthur’s troops achieved the summit, many Confederates had already begun their retreat toward Granny White Pike and Franklin Pike. Those who remained were captured or killed.

The Fate of Col. Shy and Gen. Smith. Among those who died fighting was 26-year-old Lt. Col. William L. Shy, commanding the 20th Tennessee, under the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith. Col. Shy, who grew up in Williamson County, Tennessee, was

Col. William L. Shy

Col. William L. Shy

killed by a close range shot to his head. His body was taken to the nearby Felix Compton house and laid on the porch with a blanket over him. His parents came from Franklin to get him. His effort to hold the hill at all cost, and his death on the summit, resulted in a renaming of the hill in his name.

His commander, Brig. Gen. Smith, surrendered, though his fate had an unfortunate end. As he was being led back to Nashville, probably on Granny White Pike, he was struck multiple times on the head by a Federal officer wielding the butt end of a sword. The officer was thought to be Col. William McMillen, who commanded McArthur’s 1st Brigade. Smith was expected to die from the resulting skull fractures; he survived, but was institutionalized for the remainder of his life at an asylum in Nashville. The street on which the Shy’s Hill trailhead begins, and where the historical marker is located, is named in his honor: Benton Smith Road.

The fall of the Confederate left flank at Shy’s Hill marked the end of the battle of Nashville. Even though the right flank had held its line in the battle at Peach Orchard Hill to the east, the entire force broke with the collapse of the west and the battle of Nashville ended with the retreat of Hood’s Army toward Brentwood and Franklin.

Shy’s Hill Now. Today, the Battle of Nashville Trust owns a portion of Shy’s Hill and leases the summit from the Tennessee Historical Society. It is protected by a conservation easement through the Land Trust For Tennessee. The kiosk, eastern slope trail, and Memorial flag plaza at the summit were placed by, and are maintained by, BONT.

The role of the Minnesota troops at Shy’s Hill and in the Battle of Nashville is memorialized in various ways, including a Minnesota monument at the National Cemetery in Nashville. On Shy’s Hill, BONT flies the Minnesota state flag to recognize the fact that Minnesota sustained more casualties at Nashville than at any other battle in which its men fought, and that they played pivotal roles during both days of the Battle of Nashville.

The best-known painting depicting the battle at Shy’s Hill is the famous Howard Pyle canvas located in the Minnesota state capitol.'

A provenance letter will be included.

We include as much documentation with the relics as we possess. This includes copies of tags if there are original identification tags or maps, as well as a signed letter of provenance with the specific recovery information.

All of the collections that we are offering for sale are guaranteed to be authentic, and are either older recoveries, found before the 1960s when it was still legal to metal detect battlefields, or were recovered on private property with permission. Some land on Battlefields that are now Federally owned, or owned by the Trust, were acquired after the items were recovered. We will not sell any items that were recovered illegally, nor will we sell any items that we suspect were recovered illegally.

Thank you for viewing!